This Friday I will be getting up horrendously early in the morning to catch a train to London. Here I’ll be meeting the many wonderful and varied people who are attending Science Online London 2010, this time at the British Museum Library. I went along to last year’s event in the Royal Institution, and thoroughly enjoyed it. It gave me an opportunity to put a face (and an accent) to most of the bloggers I’d been reading for some time, and meet a huge number of new faces. Also like last year I be at the wonderfully informal FringeFrivolous rooftop debate.

For my own part, I have always been enthusiastic about communicating science. As to whether I succeed at this (or not) in my writing I have absolutely no idea, but then again, as I am not a professional science communicator, it never quite seemed to matter. However, I do love to talk about science more. On the conference circuit I fair pretty well in giving talks, but outside of academia I have bent the ear of many a friend, and enjoyed the rare opportunity to hold the rapt attention of roomfuls of school children, or humanist societies. These make me feel great!

However, given the thematic nature of this blog and my mission being to keep the issue of bugs and drugs in the public domain, it’s time for me to put a more concerted effort into up-skilling on communicating ‘as a scientist, to the public’ (whether I get paid for it or not). Of course, we’re fortunate to have the likes of Maryn McKenna (the journalist and blogger behind ‘Superbug’, the book and blog) who hits the subject with her inimitable journalistic verve, but I can’t say I’ve encountered many scientists in the field giving their perspective.

I began this blog off the back of the NDM-1 story because whilst representative of an ongoing serious issue of multidrug resistant bacteria, it comes at a crucial time in the budgetary planning of future science funding. The recent media furore focussed on the lack of antibiotics (in between over-hyped commentary on cheap-ops in India), but failed to mention any of the reasons why most big industry doesn’t want to touch antibiotics with a barge pole (economic in-viability), or any of the academic involvement in resolving this problem (needless to say that it is the efforts of academic labs that we even know we have a problem!)

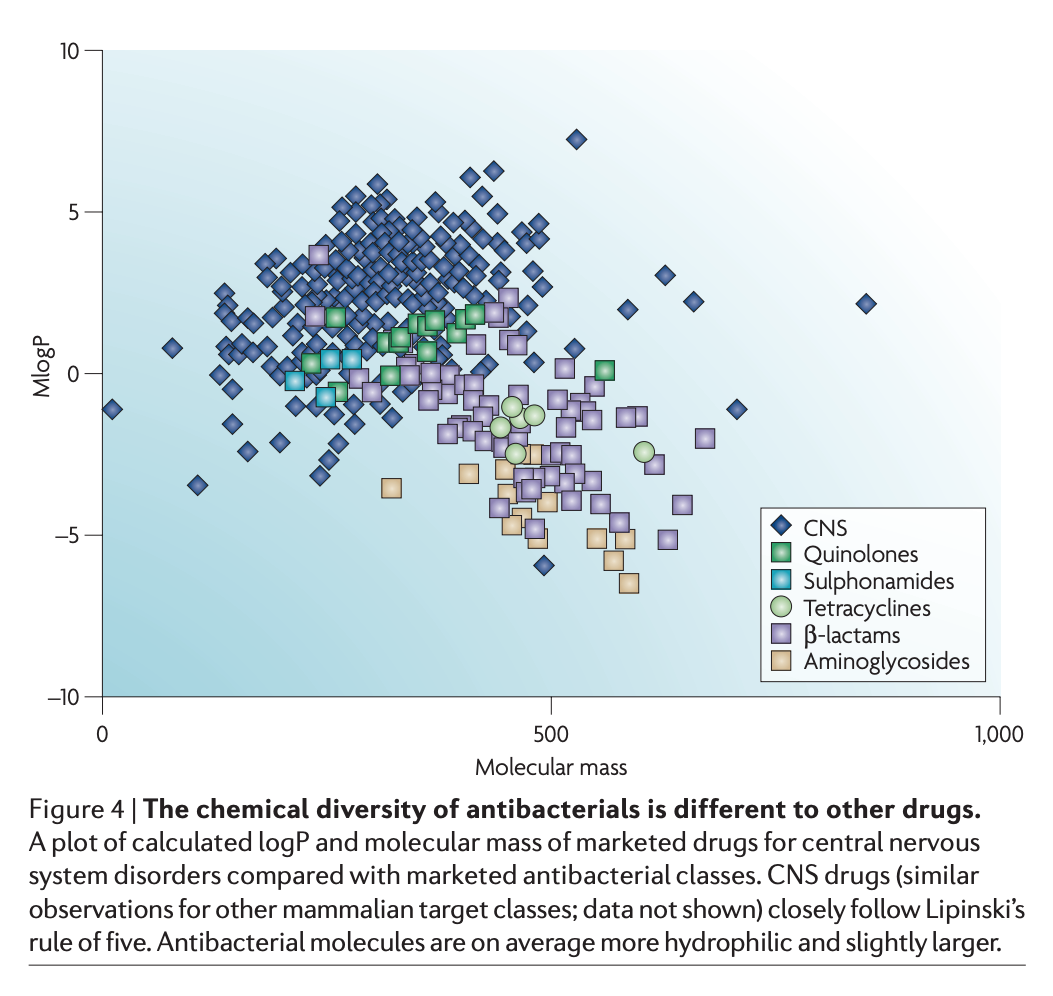

So what of it? Between 1995 – 2001, the team at one of the remaining biggest players, GlaxoSmithKline, spent $14m for each drug ‘lead’ identified over a period of 7 years (they identified 5 ‘leads’ in that time); remembering of course that a ‘lead’ may well never make it through clinical trials. One of the potential quick-fix options was screening of the pharmacopoeia, the pharmaceutical back-catalogue of drugs developed for everything from bone-loss to cardiac arrhythmia, for new leads. Companies have spent millions assaying such compounds, and derivatives thereof, to see if they can also hit a bacterial target. However, they haven’t yielded the kind of hits that were hoped. One of the reasons cited for this is that whilst the majority of therapeutic drugs obey Lipinski’s ‘rule of five’ (a set of molecular properties that define a good therapeutic drug), antibiotics don’t follow these rules.

Image from Payne et al. (2007) Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 6: 29-40 [ link to pdf ]

Image from Payne et al. (2007) Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 6: 29-40 [ link to pdf ]

Thus what are needed are truly novel chemicals; bat-shit crazy, funky, out of the box new chemicals developed by willing, well-founded and eager chemists…..but where are the chemists? Hell, where are the chemistry departments?

You might wonder that such problems are incumbent in all drug discovery, but then most ‘lifestyle’ drugs, the preferred pot of gold for big industry, have a relatively long shelf life. Not so antibiotics: most infections don’t last long, thus people don’t need many packets; physicians are told (correctly) to reserve their use only for bacterial infections (not colds/flu); moves are afoot to ban/scale back agricultural use = not much return for their investment. Then, just when the chips are down, resistance to your new drug is observed in the clinic and the death knell of the drug’s usable life is sounded.

Physicians and industry also want to treat a ‘disease’, not a multiplicity of different infections; but how do you treat a disease like pneumonia with a single antibiotic? Pneumonia can be caused by any of eight completely different bacteria (or multiples thereof), some species of which have as much in common with each other as a human does with a paramecium [ pdf ]. There is a fundamental disconnect between the popular models of drug development and the issues at hand with antibiotic development.

Of course, if industry sees no economic viability in antibiotic drug development, we need to sweeten the deal; one way to do this is offer public money. I hear you gasp, but think about it, this is a global issue and treatment programmes for HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria are the great success stories of what happens when public support, political clout, industrial partnership and a huge pot of cash collide. Of course, in these days of pharma-bad / dolphins-good, no-one is going to throw any public money at industry. One of the best accommodations is for partnerships between industry and academia. These are already a mainstay in microbiology (because if we relied on research council money we certainly wouldn’t still be here!), but it actually relies on the academic partner still being here.

Industrial partners can out-source a great deal of the legwork to academic partners for relatively low cost, increasing the network of players scanning for new drugs, informing new directions and finding. However, I can already run off a list of ten names of highly trained researchers in this field who have left the field over the past 8 years. At this time we’re facing another budgetary crisis in science funding and we must, at all costs, prevent a further loss of both industrial and academic research capacity involved in antibiotic research.

The public needs to be aware of the strong part academic research will have to play in developing new courses of action in the advent of new ‘superbugs’. For all the hope I have that there are academic solutions to better strategies of antibiotic use, anticipating and preventing resistance, better surveillance, and identifying new drug targets in bacteria (or better approaches to known targets), these are all rather like architect’s plans when what we need right now are some bricks in the oven.

Look forward to seeing everyone at Science Online 2010.

[This post was restored from a WayBackWhen archive. It was originally posted to a blog called ‘The Gene Gym” that began life on the Nature Network in 2010, and then moved to Spekrum’s SciLogs platform.]